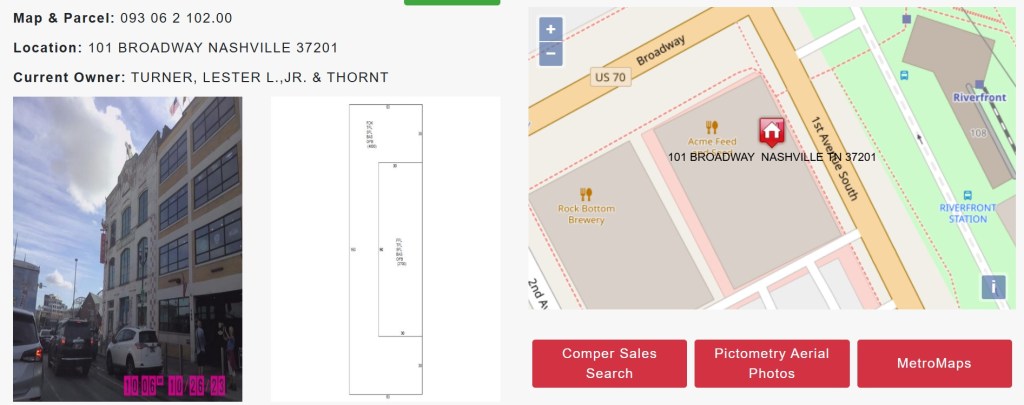

Local Nashville news has been abuzz about the huge tax bill faced by Lower Broadway’s Acme Feed & Seed for the 2025 tax year. Located at 101 Broadway, at the start of the historic Broadway honky-tonks and overlooking the Cumberland River, it’s a prime property on a stretch that has continuously set (and re-set) new records for property values.

For the past 5-7 years, asking prices for Broadway honky-tonks have reached unimaginable heights. You can buy Jelly Roll’s bar for $100Million. Jon Bon Jovi’s is being offered for $130Million.

That’s great for the property owners’ balance sheets, but it’s bad news when the Metro Nashville Assessor starts paying attention. (Increases in tax appraisals generally mean higher taxes.)

2025 Metro Real Property taxes come due later this week, and, if this past week’s news is any indication, nobody is more worried about their 2025 tax bill than Tom Morales, the owner of Acme Feed and Seed.

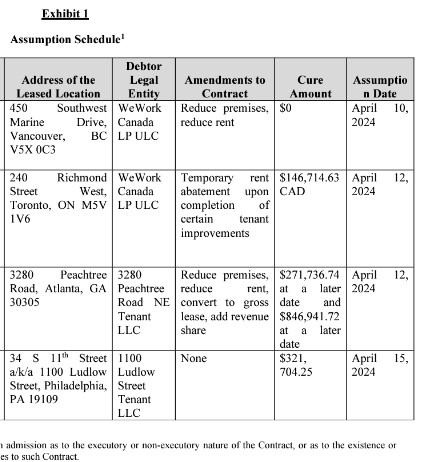

As a result of the recent re-appraisals, for 2025, the property is appraised at $50,049,200, a huge jump from 2021’s value of $9,577,900.

The tax bill? $589,259.28 (and has not yet been paid).

The public response has been mixed. Lots of people won’t ever feel sorry for somebody whose property value goes up $40+ million dollars (and would fetch far more in a private sale), but those people are missing a key point: Tom Morales doesn’t own the property, per the Quitclaim Deed.

Why, then, would a renter care about the property taxes?

My guess is that he probably signed a triple net lease (often written as “NNN”).

In simple terms, a triple net lease is a lease where the tenant pays not just “base” monthly rent to the landlord, but also all of the property’s operating expenses: real estate taxes, insurance, and common area or maintenance costs. In short, the landlord owns the building, but, per the lease, the tenant agrees to pay all of the expenses of the building, usually in 1/12th increments throughout the year as “additional” rent.

If you don’t work in the commercial leasing realm, it probably blows your mind to think that, as a tenant, you’d be responsible for all of the expenses of a property. Why not just buy the building yourself?

It’s a common leasing structure. From the tenant’s perspective, they can operate out of property, without the cash, credit, or long-term obligations of purchasing an expensive building. Acme Feed and Seed may not have had the credit (or desire) to own a $50 Million property, but it can get it via lease. And what a property it is: On New Year’s Eve, nearly 250,000 people rang in the new year at Acme’s front door, with TV and media coverage you can’t buy.

From the owner’s perspective, a deal like this ties up lots of cash or credit on an fixed asset, but, at least, they don’t come deeper out of pocket for the operating expenses. It sounds like a great deal, sure, but being a landlord still carries risk. Ever hear of a bar going out of business and being vacant? Who pays the mortgage, taxes, and expenses in that situation?

At the end of the day, a commercial lease is a contract, and the two parties are free to agree to whatever they want in a lease. They can allocate taxes, insurance, and maintenance responsibilities in any way, and a Tennessee court will hold them to that bargain, no matter how unfair the unforeseen results can be. A contract will be enforced according to its plain language.

With that in mind, for any tenant considering a triple net lease on a property with potential for this sort of wild change, I’d recommend that the tenant consider a provision to mitigate the risk this could happen.

No landlord would be willing to voluntarily bear this tax increase, especially if the tenant retains all of the use and benefit of such a valuable property. (From the landlord’s perspective, the tenant is, now, paying under-market rent, as if the building was still worth a paltry $10Million, right?)

Instead, this lease could have included a provision that allows the tenant to opt out and terminate the lease, if the tenant could prove this increase in the tax cost was a material change. In that situation, the tenant would have an option to get out of the lease and, on the other side, the landlord would be freed from “the burden” of being bound by an under-market lease and could, then, attempt to enter into a new lease based on the $50MM valuation or capture the value via sale. (In short, the landlord would probably happily terminate the lease and see what the free market says about all of this.)

Without that, a tenant can only hope the landlord will pitch in and help with this cost. If I had to guess, all of this hit the local news after the landlord declined to pay the tax bill.

Broadway has changed a lot since Acme first opened their doors 15 years ago. Even the best commercial real estate attorneys could not have foreseen this when drafting this lease, but it’s something to think about on the next honky-tonk lease.