A recent case involving Deja Vu Showgirls Nashville (warning: do not click that link) offers a useful map for a judgment creditor to follow where a garnishee fails to answer a wage garnishment.

In the case, One Main Financial Group, LLC v. Edward Hackney, Jr. (Davidson Co. General Sessions Docket No. 23GC8323), the Plaintiff served a wage garnishment on “Deja Vu Showgirls, Attn: Payroll.”

As you know, employers must respond to wage garnishments in Tennessee within 10 days; if they don’t, the employer risks being held liable for the entire Judgment debt.

In the Sessions case, there was no answer filed, and Plaintiff filed a Conditional Judgment, asking that the full $14,000.56 judgment against Hackney be made a judgment against Deja Vu. Once a conditional judgment is signed, the court then sets a final hearing on whether to enter a final judgment against the non-responsive party.

When Deja Vu failed to respond in any way to the wage garnishment or the conditional judgment, the Court granted a final judgment against it for the underlying debt.

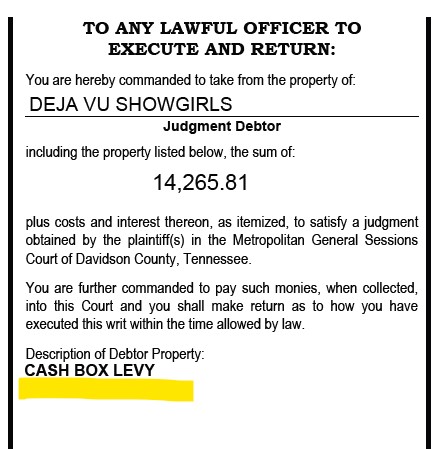

Unsure of where Deja Vu banks or holds assets, the Plaintiff issued a levy instructing the Sheriff to seize the “Cash Box.”

Plaintiff’s logic was sound. A few weeks later, the Sheriff went to the establishment (on a Saturday!), seized all available cash (well, the cash up to $14,634.00, the amount owed under the Judgment), and paid the funds to the Court Clerk.

Some thoughts?

Don’t ignore wage garnishments. Ever. Who knows if Edward Hackney works at Deja Vu or, even if he did, would he have been paid $14,000 during the garnishment. Due to Deja Vu’s failure to respond, the actual facts are irrelevant; Deja Vu became liable for the full debt simply because it never responded.

It’s rarely too late to answer (until it is). A conditional judgment is a “warning shot” to a non-responsive employer/garnishee, and, if a response is filed before the final hearing, the conditional judgment is vacated.

Was the cash levy valid? A judgment creditor can levy against personal property of the judgment debtor, including cash. This is often called a “till tap,” and it’s a smart move anytime you’ve got a judgment against a debtor with cash in their pockets, in their possession, or in their cash register.

In the end, the best test of collections process is whether it works. Here, Plaintiff got a little bit lucky. The Sheriff served this levy on a Saturday, presumably when the business had ample cash on hand (I actually didn’t realize the civil process unit served process on weekends).

And whoever was manning the cash box didn’t raise any issues related to service or the accuracy of the corporate name issue at any point–whether at the time of the levy or before the money was disbursed. (Looking at the corporate records at the Tennessee Secretary of State, an argument could have been made about some things.)

Sometimes, a little bit of luck makes all the difference.

My advice is to always take as much care in issuing levies as you would when filing a lawsuit. That means getting business name exactly correct. A judgment in this situation is like any other judgment–you have to get valid service of process and party’s name correct.